There’s a statue of Beethoven, in Los Angeles, in a place called Pershing Square, where a man named Nathaniel Ayers Jr, homeless, schizophrenic, and lost, would find himself, in the gaze of the composer, when he could, playing a violin with only two strings. Two string because the rest were broken. He had a cart he would push and drag around the less affluent areas of town, filled with his precious things, like bedding, flags, brooms and dustpans, and clothing. He had a chair leg in case of muggers.

A columnist for the LA Times, Steve Lopez, stumbled upon Mr. Ayers one day and learned a few things about life.

A book, written by Mr. Lopez, called “The Soloist” based on Nathaniel’s life, is available (ironically, there are two books called The Soloist, so look for Mr. Lopez’s). I highly recommend it.

There’s also a movie starring Jaime Foxx as Nathaniel and Robert Downey Jr. as Steve. It is excellent as well.

This post is the 500th entry in my rambling journey in the strange Art we call “Bonsai”, chronicling all the pinnacles and dark pitfalls that my trip offers. Getting to such a big number (I mean, FIVE HUNDRED, c’mon, that’s a big deal) is surprising to some (me being one) and a little discouraging to others (I’m sure).

I am, after all, that annoying smart-ass bastard in the back row of the audience that’ll ask the teacher “Why?”. It got me in trouble during my formative schooling years, enough so to encourage and codify my natural distrust of authority into a philosophical, aesthetic, and political way of thinking.

And it still gets me in trouble today.

Speaking of today and today’s momentous and important blogpost, I’m going to do what got me into the professional end of the Bonsai World: carving deadwood.

The first tree is a buttonwood. Here are some establishing shots:

Yeah, basically a broomstick.

Yeah, basically a broomstick.

The second tree is a bougainvillea:

Front side

Bougies and buttonwood both present and keep deadwood in totally different fashions, and the difference in carving them is marked as well. But, the principles are the same.

Bougies and buttonwood both present and keep deadwood in totally different fashions, and the difference in carving them is marked as well. But, the principles are the same.

I was a woodcarver before I got into bonsai, carving faces and shapes into found pieces of wood. In fact, my main tool I use for finish carving, a MasterCarver series flex-shaft tool, is older than my bonsai career, more than twenty years old, and I’ve only replaced the actual flex shaft, with no problem on the electric motor (funny thing, I once, on a Facebook thread, described a Dremel tool as being worthless for serious carving as I have burnt up four of them. I think I may have intimated the the manufacturer makes them for amateurs to use very rarely and they were more of a gift than a useful tool. That did not go over well with some professional bonsai carvers; they thought I was calling them amateurs. I wasn’t, but that’s how these guys perceived it).

In my quest for carving knowledge (I am a self taught kinda guy, what they call an autodidact, in Japanese the quest is called 独学 Dokugaku. Self study). I read books, looked at sculpture online, and, most importantly, studied works in person. I learned an important principle: carve shapes, not lines. The shape of an object is more important than any details that you add later. If you’re so stuck on the details, like texture or line, you’re not carving, you’re drawing on the piece. The way light hits a three dimensional object is what will give your carving movement. Not lines scribed on the surface.

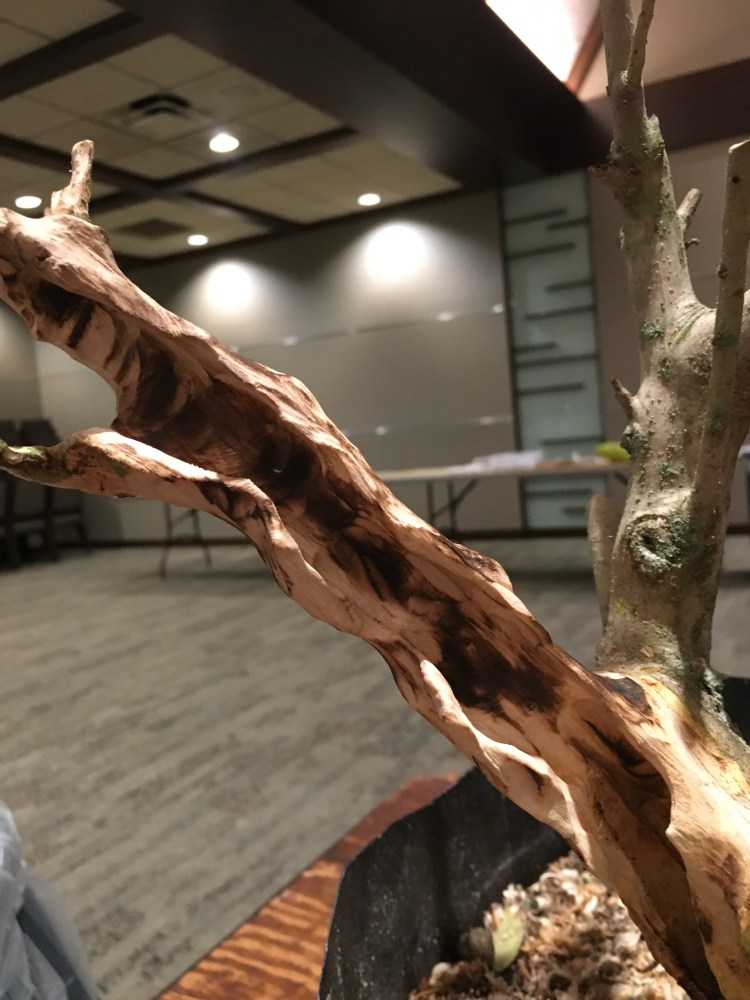

This was after the first pass of carving on the buttonwood. The first pass is to create taper, define some shape and movement, and to make some hollows.

The first carving was done with a die grinder and a Ninja Bit from Samurai Tools.

Below, the pics show the result of using the next size down bit, the Geisha.

After the shape is defined, the next step is some fire. The reason is two-fold, to remove tool marks and to help in the next step of artificial ageing.

A trees wood grows in lines and layers we call the grain. It’s made of a hard and a soft layer of wood and it’s the soft layer that rots more quickly (and burns first too). The fire is to help get rid of the softer layers.

The next step is to detail it with a wire wheel, brushing age lines into the wood.

If the tree were bigger, I might make those lines deeper, more defined, but a small piece gets smaller details.

Buttonwood deadwood is defined by salt and sand spray eroding the wood. You get sharp sticks like a juniper’s deadwood (which erodes differently as well, but that’s another blogpost), and you do get broken edges, from crocodiles and tourists, and hollows from ants and borers.

The before

The after That’s all on that one. For now. The next process is lime sulphur, then hand brushing with a brass brush, more lime sulphur etc. But that’s for the owner of the tree. We thought it best for him to drive home and put the lime sulphur on it instead of having to endure the rotten egg smell for the 2-1/2 hour car ride home.

That’s all on that one. For now. The next process is lime sulphur, then hand brushing with a brass brush, more lime sulphur etc. But that’s for the owner of the tree. We thought it best for him to drive home and put the lime sulphur on it instead of having to endure the rotten egg smell for the 2-1/2 hour car ride home.

In my art schooling, I took a class in watercolor. It was a half year course taught by an instructor that wasn’t my main teacher. She was also the ceramics and drafting teacher.

My experience and main thrust in art at the time was making highly detailed pen and ink, or pencil drawing, and, oddly, arcrylic and mixed media fine art paintings. Not abstract, mind you, my stuff had meaning…..

Anyway, the technique in watercolor is really the technique of not painting. Letting the white of the page shine through, and the colors should be translucent. It’s not a heavy application of pigment but a light touch, letting the water move the paint over the surface the same way frost grows over a car windshield in late fall.

There is white watercolor paint, but you’d be better off throwing it away. Let the medium work, let it flow the way it’s supposed to, you’re job is to guide it only. Washes, dry brushing, speckling drops of paint randomly on a near finished piece. That’s watercolor.

Now, for the bougie.

The bougie’s wood is very different than most wood. It is technically a “bine”. A plant, much like a vine, that grows in long shoots and likes to grow up, hanging on other trees or structures. It’s a small technicality, but a vine has tendrils that attach to the climbed structure (think ivy or grape). A bine, on the other hand, usually has thorns that tangle onto structures.

And stab the unwary bonsai practitioner.

The wood tends to rot.

Well, mostly.  A lesson I learned from the USA’s original Master Carver: if the wood of the bougie is thin enough, we can preserve the deadwood with lime sulphur and a wood hardener.

A lesson I learned from the USA’s original Master Carver: if the wood of the bougie is thin enough, we can preserve the deadwood with lime sulphur and a wood hardener.

First pass with the die grinder.

The strategy is to hollow the trunk out and make caves. A real 3D carving.

Then the torch to soften the tool marks.

Then the wire brush to bring out the grain.

The wood on this piece is mostly dry, and, though I like the raw wood look, I know I’ll lose some details if I don’t lime sulphur it. And I have this tree for a week so I have time to finish.

For those using the lime sulphur for the first time, it goes on yellow/orange. Don’t worry, it fades to that grey/white color over a few hours. Even more so if you stick it in the sun.

This pic shows it, in the back of the car just before I delivered it to my client.  I just know that there will be the comment saying “I don’t like the white color that lime sulphur turns the wood”.

I just know that there will be the comment saying “I don’t like the white color that lime sulphur turns the wood”.

My view, sometimes it’s appropriate, sometimes not. And it always fades anyway.

Here, on this piece, I believe it is appropriate. Why?

Here, on this piece, I believe it is appropriate. Why?

A few weeks later, where I gave a demo on a European olive for the Shofu Bonsai Society of Sarasota, the tree was brought in by my client as a prop for the presentation.  You see it has faded a bit. But still, that grey/white deadwood contrasts perfectly with the bright red bloom.

You see it has faded a bit. But still, that grey/white deadwood contrasts perfectly with the bright red bloom.

Now, imagine it fully bloomed out!

For the curious, here’s the European olive I carved for the club.

This wood was mostly new and still wet, so it needs some time, but I have the shape, and the fire and brush technique worked.

The tree needs to grow, but the bones are there.

My first demo and workshop where I was the teacher was at a Wigert’s Bonsai open house. He heard I had carving tools and asked me if I wanted to teach the class, only on seeing some of my wood sculptures (here’s a Blog post on a simple tiki carving I did). He hadn’t even seen my bonsai carving. But Erik has a way with bringing out the best in people by pushing them past what they think is their limit. Look at the talent of his students, and of his two star teachers, Jason Osborne and Mike Lane.

I could carve, and Erik saw that the skill of creating a face could translate into bonsai. This is important because art principles, any art principle, has everything to do with bonsai.

Bonsai is an Art.

So how does it all tie together? My 500th post, the story of a schizophrenic musician, bonsai, carving, and art? I could talk about teachers who’ve pushed me in English or art, or friends that encouraged me. I could extrapolate aesthetic theories from obscure 17th century artists, modern horticultural practices, the psychology of interpersonal dynamics within an insular community.

I’ll let you draw your own conclusions.

There’s a lot in this post already, I’ll save everything else for #501, and beyond.

Dude…I need help picking my jaw back up off the floor! Nice work there my friend.

LikeLike

Congratulations!

LikeLike

Well done, my friend! Wishing you many more years of success!

LikeLike

awesome, love the carving … the pot?

LikeLike

The buttonwood is in a bunzan pot. The bougie is a pot made in Italy, a mass production one

LikeLike

Congratulations on 500! i always learn something from you. Here’s to 500 more!

LikeLike

Nice job…Amigo

LikeLike

Really you are great artist dear….i like this…… very nice… Keep it up

On Tue 22 Oct, 2019, 9:27 PM Adam’s Art and Bonsai Blog, wrote:

> adamaskwhy posted: “There’s a statue of Beethoven, in Los Angeles, in a > place called Pershing Square, where a man named Nathaniel Ayers Jr, > homeless, schizophrenic, and lost, would find himself, in the gaze of the > composer, when he could, playing a violin with only two strin” >

LikeLike