It’s been two years, at least, since I collected this tree. That should be enough time for it to have gained strength. I’m still not going to be too rough on it though.

It was tough to identify this one but after an exhaustive Google search, I believe it is a blackjack oak (quercus marilandica). Although it’s leaves resemble a chapman oak (quercus chapmanii)…

….they grow in dry areas and I collected this one in a wet-ish area. Which then made me think of a water oak (quercus nigra) but they have a smooth bark and this one is rough and gnarly.

….they grow in dry areas and I collected this one in a wet-ish area. Which then made me think of a water oak (quercus nigra) but they have a smooth bark and this one is rough and gnarly.

I also thought about myrtle oak (q. myrtifolia) but it grows in dry areas and has a smooth bark. So with all that said, I’ll call it a blackjack oak. If a real arborist out there thinks differently, please comment.

It’s a “red oak” native to not only Florida, but of most of the south east of the US from Long Island to Florida and from Nebraska down to Texas.

I’m not sure of the front yet but that’s on the agenda today as well as to put it in a wider pot, with a little better soil, carve the chopped top, and set the branches with wire. It may seem odd to do all that now in November, on a deciduous tree (the blackjack sometimes will keep its leaves through the winter here, but it is technically dormant in the winter) but, from the pioneering work of Erik Wigert, we have learned that it’s possible to collect (and therefore, repot) oaks at this time, in Florida. The belief is that, since winter is so dry and Florida trees’ roots (especially live oaks, which had been hard to collect because of the long tap roots) continue to grow through the winter and therefore end up being so far from the trunk, it’s best to collect the trees just as they go dormant and those feeder roots are close in to the trunk. We could be wrong about why, but his and my success rates are close to 100% when we collect in November, in Florida.

With that said, first up, the roots.

Out of the pot. I’m not seeing too many roots. This tree is supposed to thrive in poor soils so maybe it doesn’t need many? It’s never wilted so maybe it’s stayed too wet and a tree doesn’t need too many roots when the water is close and easily available.

Out of the pot. I’m not seeing too many roots. This tree is supposed to thrive in poor soils so maybe it doesn’t need many? It’s never wilted so maybe it’s stayed too wet and a tree doesn’t need too many roots when the water is close and easily available.

That root spread and the slant are why I collected the tree. And that bark! Always look for something interesting or unique when digging up a tree from the wild. If you just want a tree and all you see are straight trunks, try harder or go home. It’s not worth the trouble digging a tree up for a straight trunk, really. It’s easier to just buy a landscape tree at that point and chop the trunk. Trust me.

That root spread and the slant are why I collected the tree. And that bark! Always look for something interesting or unique when digging up a tree from the wild. If you just want a tree and all you see are straight trunks, try harder or go home. It’s not worth the trouble digging a tree up for a straight trunk, really. It’s easier to just buy a landscape tree at that point and chop the trunk. Trust me.

The glamorous, high end pot that my blackjack will call home for the next few years is the one on the right.

Awesome, ain’t it? Im using a mix of my regular SuperMix™ and some regular potting soil cut 50/50 with perlite.

Now, after getting my hands dirty (if your hands aren’t dirty, then you’re not really doing bonsai now, are you?) I’m ready for the branch work.

In Florida, it’s sometimes hard to tell if a deciduous tree is dormant. Many of them don’t really change colors like up north.

It’s subtle things that one must look for. Like the brown edges and yellowing of the leaf veins.

Our native trees must not need to recycle their chlorophyll like trees up north. Maybe because of the amount of sunshine they just make so much sugars there’s no need to have to bring it back in.

To expand on the “why” a tree may drop its leaves in autumn, briefly: a tree makes energy through photosynthesis using the green chlorophyll in its leaves. Some trees have adapted to the low light conditions in the winter by going dormant (not freezing has a part to play as well, we will get to that). Because chlorophyll takes energy to make, a tree will pull that chlorophyll back in and reuse it next year (that is an extremely simplified explanation).

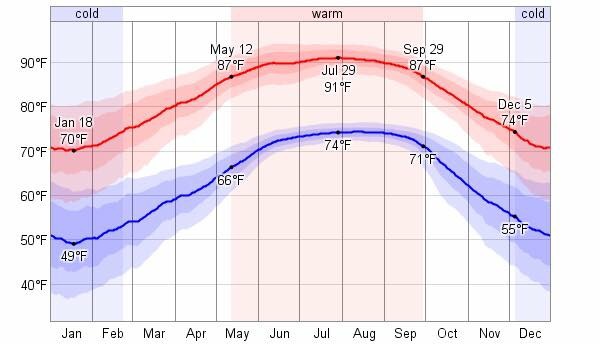

Now, it is lack of light that triggers dormancy, not temperature. But, it is temperature that triggers dormancy break. Applying that seeming dichotomy to Florida, native trees can handle the extended growing season and the fluctuating temps in the winter, I believe, because they, one, have a summer dormancy (it’s not uncommon to see bright red leaves on acer rubrum or orange needles on taxodium distichum in July/August) and two, the sheer amount of sunlight available to them to make energy. Non native trees can’t handle going dormant twice a year, they just don’t have the capacity to make enough energy (think: acer palmatumn or acer ginnala or larix laricina) and they wither and die after two or three years. Many people think it’s the heat that kill those northern plants, or maybe fungus (which might play a role) but it’s really the lack of winter dormancy (so, indirectly, it is heat. But not our summertime heat, which rarely gets above 95, but the wintertime lack of cold stimulating early growth). I was just actually having a discussion on zelkova with Ryan Bell of japanesebonsaipots.net and he thinks I can grow them here. All the old timers in Florida say “You can’t grow that fuckin’ tree here, don’t waste your time”. He says that they’re grown in Taiwan, which has a similar climate to me and therefore I should be able to. He gave me a test. He asked, “which one is Orlando and which is Taipei?”

I got it right, can you guess which is which? They’re pretty similar.

I told him to send me a zelkova to experiment with. We will see.

Anyway, back to the blackjack, Mack! This is new growth.

Don’t know why it’s there but, like I said, it’s a struggle to keep our deciduous tree dormant in autumn/winter. Time for a short lesson on wiring.

Don’t know why it’s there but, like I said, it’s a struggle to keep our deciduous tree dormant in autumn/winter. Time for a short lesson on wiring.

Anchoring the wire is key. When wrapping it, always hold the wire firmly.

Using two hands, anchor one side onto a branch wrapping one way (say counter-clockwise).

And wrap the other side the opposite way. This holds the wire and the branch from moving and damaging the branch when it’s time to bend.

And wrap the other side the opposite way. This holds the wire and the branch from moving and damaging the branch when it’s time to bend.

Branch to branch wiring

At the end of the wire, the final twist should be underneath.

At the end of the wire, the final twist should be underneath.

This allows you, when placing the wire, to bend the branch tips up. This mimics the natural tendency of branches, growing up towards the light.

When ending big wire and continuing new wire, it’s a better anchor to twist the skinnier wire around the thicker wire.

First, twist the heavy wire’s end with Jin pliers.

Then wire as usual, starting several twists in.

When you get to the end of the heavier wire, wire around the end.

When going from primary to secondary branches, I always use the staple, or “U” method of wrapping the wires going in opposite directions when anchoring from branch to branch.

To confusticate the intermediates out there, here’s an example of when you should cross wires. We have a dilemma here.

If we continue without crossing, the wire won’t be supported and could damage the branch.

So is you cross the wire like so.

So is you cross the wire like so.

Around the underneath, the anchor is strong. The only real reason that you want to avoid crossing is because it’s ugly. Like my dirty hands. Or because when you cross, you sometimes don’t get a good anchor.

Now it’s time to place the branches.

I can teach you how I artistically place my branches. But that’s how I see my trees. Instead I would rather you try to mimic what you see in nature, not how I see it.

I can teach you how I artistically place my branches. But that’s how I see my trees. Instead I would rather you try to mimic what you see in nature, not how I see it.

When bending, always use two hands and support the bend.

Now, here’s something you’ll never see on those “pretty boy” blogs. A mistake.

Can you see? When I wired, I should have wrapped around the main branch. When I moved the branch, it broke at the junction.

Can you see? When I wired, I should have wrapped around the main branch. When I moved the branch, it broke at the junction.

If I had done this…..

If I had done this…..

…it would not have cracked. Dumbass. I needed that branch.

The chop needs just a touch of carving.

Not much, just enough to make it natural. I might extend it down the trunk but that’s getting boring. I’ll wait and see what happens. The tree will tell me what to do.

Not much, just enough to make it natural. I might extend it down the trunk but that’s getting boring. I’ll wait and see what happens. The tree will tell me what to do.

Right now it’s saying, “Stick a fork in me, I’m done!”

Left side:

And the front.

Here’s how I see the tree in a few years.

I give it just a little fertilizer, just a light sprinkling like pepper on eggs really. And I’ll keep it in the shade for a few weeks. Then partial sun. I wholly expect it to push new growth and that should be ok because there are some years we can have a hurricane in November and that means both partial defoliation and even root damage from the high winds. Just about what I did today. You can call me Hurricane Adam.

Anyway, the next post might just be a blog on making soup. It’s that time of year and cool nights call for a nice hot pot of soup. And it seems that the blogs that make money and get the most reads are foodie blogs. And the family could use the money. Adam’s Art and Hummus? Has a ring to it, don’t you think?

But of course that means I’ll need to clean my stovetop. Damn. I’d rather wire a tree.

Regarding Taiwan vs Orlando. Taiwan has something Florida doesn’t have – high altitude. There is tremendous variety in what species can grow across Taiwan due to altitude. As you would imagine the altitude changes the microclimates making them cooler than places without altitude like Florida. The topology of Taiwan also has an effect on how the ocean currents affect the island. Check out the eastern coast of Taiwan on a topographic map. Finally although a relatively small island, latitude also has an effect on what can grow where in Taiwan. It is not a monolith when it comes to climate zones.

LikeLike

There is that Rob. I was thinking the same thing about the mountains. They can definitely grow shimpaku better than we can. Like I said, we will see what happens.

LikeLike

Great tree! This spring I think I will look for some native trees to dig. I still don’t understand why to use potting soil in this case because my understanding is that faster drainage= faster growth and that would be desired when recovering a collected tree. Also, why do you keep the branches so long rather than prune them short and build ramification by repeated close cutting before styling the tree?

LikeLike

Drainage in a deeper nursery container is faster than in a shallow bonsai pot and could possibly cause the tree to dry out faster than you want if you use straight bonsai soil. Plus, if you’re collecting a lot of trees at one time, which tends to happen, you can’t afford that much bonsai soil. But I always cut it 50/50 with perlite (which could be used as bonsai soil in a pinch anyway).

I was going to bring up the long branches in the post but I cut that part out. I was going to point out the general teaching that, to thicken a branch, you first grow it long then cut it back. But you can still thicken a branch by building ramification.

In the future I will probably still cut it back for taper but that’s how long I want the branches to be in the final design and I have to look at it until then.

LikeLike

Adam, first let me say it was great to meet you at Wigert’s Open House. I have a question about how you create the foliage effects in your last picture of the oak. What software app are you using to create that image?

LikeLike

Thanks, it was nice meeting you too.

The app is an iPhone one called PE-FOTOLR. There’s a free one with ads and a premium one. I use the free one. You paint with your finger

LikeLike

Thanks for the help! Now all I have to do is translate that to an android app. I think it will help me see where I want my own trees to go.

LikeLike

Zelkova is similar to Chinese elm, which seem to do great in your area, so I’m surprised so many claim you can’t grow them.

LikeLike

Inspiring

How does it look now, in 2020?

LikeLike

I’ve since sold it and I’m not sure, sorry

LikeLike